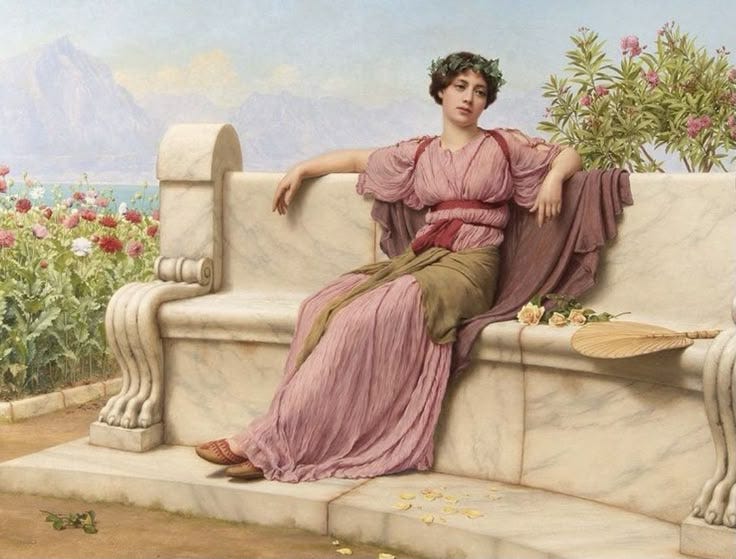

I’m going to say it: I’ve been dreaming of leisure again. There is this part of me (I am not unique in this, I’m sure) that wants to be freed from the weight of ever having to think about securing plans for the future. I want to need to not do anything. I’d like to exist knowing that I could not do anything for months or years and absolutely nothing would be impacted by this.

I’m talking about the kind of leisure that involves escaping to a warmer climate for three months, choosing not to work, and alternating between lounging and eating fresh fruit on a morning walk. And then after I’m all rested up, I’d settle into a routine of reading deeply, writing a little, and maybe meeting new people. Like I said, I think most people, if not everyone, would like to have the sort of financial security where this is possible. The only difference lies in how people choose to spend their free time, but, without a doubt, everyone would prefer being that financially secure.

I suppose there isn’t much that can be done about that, but for those of us who, in the context of our messy and complicated modern world, are comfortable enough to not worry about food and housing and entertainment, can and should set out to enjoy the leisure that is available to us. It’s important to have time that can be your own and, as young woman with no children and no dependents, I should feel like I hold power over my own time.

The kind of leisure I’m talking about isn’t the kind found in stolen moments between obligations, not the kind that has you scrolling on your phone, or the kind that has you panicking over what to do now that you are finally free. It also most definitely isn’t the kind where you’ve allocated yourself time to rest as a desperate attempt to fix your recent procrastination which leaves you wallowing in guilt of wasted time.

No, this is the kind of leisure that comes from understanding that leisure is not just the absence of work, not just passive entertainment or the mere physical act of reclining, but that it is something more deliberate. Leisure is a space where you think, you create and you exist without needing to justify, without needing to plot desperately. A long afternoon spent writing without needing to check the clock or a passionate conversation in the evening after dinner without need of a conclusion. True leisure involves engaging with meaningful things not for monetary gain but for the sake of curiosity.

Granted, to be able to experience this kind of leisure means that one must have the luxury of time, but I don’t believe that every wealthy person is truly a person of leisure. As we know, wealth in this world seems to be wasted on those who deserve it the least.

So, what does it mean to embrace leisure when you have the opportunity to? What does it look like when curious women are just as fond of leisure as they are knowledge?

Please join me in finding out.

Sections:

Dear reader, you are cordially invited to the Salon

An introduction to the Salon

Les Précieuses

Les Contes des Fées

Reflections: A Salon Discussion

Dear reader, you are cordially invited to the Salon

You have been hand-selected for an invitation to one of the most coveted gatherings in 17th century Paris. You have been invited to a salon hosted by one of the city’s leading salonnières.

What is a salon? Well, it’s more than just a party and more than idle chatter takes place in one. A salon is where the world is shaped. Here, ideas are tested, reputations are made, and artistic merit is explored. But don’t forget your etiquette. You had better listen with intent and if you’re going to say something, it better be worthy of contribution.

Now, step inside. The conversation has already begun.

⚜ An introduction to the salon

Salons first emerged in Italy in the 16th century and continued to be popular in the country all the way through to the 19th century. In France, salons were introduced in the 17th century from Italy.

The French word salon is said to have first appeared in the mid 17th century. It is similar to the word used by Italians for the gathering, salone. A sala in Italian is a room and a salone is a big room— a reception hall in a mansion, more precisely.

The first leading salon in France was run by an Italian-born French woman, Catherine de Vivonne who was the marquise de Rambouillet. She started the salon Hôtel de Rambouillet in the early 1600s and it ran until her death in 1665. On the basis of Italian codes of chivalry, she developed the rules for the etiquette of the French salon. Catherine hosted the Chambre Bleue (after her room decorated in blue).

Women were central to salons as their hostesses, giving them indirect access to political and literary circles. Aristocratic women could, through this, have the power to shape debates and promote writers or philosophers they favoured. The women of the salons, the salonnières, were expected to run these events and organise them. They would select the guests, decide the topics of discussion, and would lead the conversations. The salonnières would also sometimes share their own writing.

⚜ Les Précieuses

Catherine de Vivonne was known for being a smart and quick-witted woman. She was born in Rome into a noble family and was married off at the age of 12 to Charles d’Angennes, who later went on to become the marquis de Rambouillet. He was ten years her senior. Together, they had seven children.

Rather than resigning herself to the coarseness and rough manners of French court life, Catherine carved out her own space. By 1620, she converted her Parisian home into the heart of the literary and philosophical world. Beneath the soft glow of candlelight in her famed Chambre Bleue, Catherine gathered the brightest minds of time.

Witty and discerning, Catherine shaped the art of conversation and laid the groundwork for the great French salons of the later 17th and 18th centuries. In the dimly lit and elegantly furnished Chambre Bleue, Catherine set the standard for polished conversation, literary refinement and cultivated wit.

For this piece, the more intellectual and philosophical content of salon discussions will not be my focus. I want to turn my attention instead to the more whimsical aspects of salon life. This includes Les Précieuses. They were a group of aristocratic and bourgeois women who sought to refine language, manners and intellectual discourse. The word précieuse was originally used to describe their sophisticated taste, although the women never used the term for themselves, but later the name took a satirical turn, particularly after Molière’s 1659 play Les Précieuses ridicules mocked their exaggerated refinement.

The précieuses were reacting to the to the rough and vulgar culture of the French court, particularly under the influence of Henry IV and Louis XIII, seeking to purify the French language. They avoided crude expressions and promoted a more poetic and elegant spoken French. Many précieuses were also writers themselves, writing novels, pays and essays exploring topics like love, virtue and societal expectations. They challenged traditional courtship norms, rejecting the transactional nature of aristocratic marriages and pushed for the idealisation of romantic love based on mutual respect and matched intellect. Unfortunately, the précieuses’ love of refinement and their playful linguistic games and inventions, topped with their idealisation of romance made them easy targets for satire.

⚜ Les Contes des Fées: The Fairy Tale genre

If Catherine de Vivonne laid the foundations of the salon as a space for intellectual refinement, then salonnières like Madame d’Aulnoy pushed its boundaries even further, blending imagination and subversion into the carefully curated world of salon culture.

Marie-Catherine, Comtesse d’Aulnoy, was also known to be a woman of wit, but she also had a taste for the fantastical. She became one of the earliest authors of what we now call fairy tales, shaping a genre that would long outlive her. Her 1697 story collection Les Contes des Fées coined the term for the genre and it was in this collection that the first story to use the name Prince Charming, Prince Charmant, was found. She was one of at least thirteen women who made up the group Les conteuses— French female authors active between 1690 and 1709 who wrote almost two thirds of the 100+ French fairytales published during this time.

Madame (Mme) d’Aulnoy was born into a noble family in Normandy and was married at a young age, like Catherine de Vivonne, although the Marie-Catherine’s future husband, the Baron d’Aulnoy was 45 to Marie-Catherine’s 15 years of age. They went on to have six children together. In 1669, her husband was accused of treason for speaking out against imposed taxes by the King (it may be relevant the fact that he was a known gambler). He ended up avoiding execution after convincing the court of his innocence three years into his stay in the Bastille and his accusers were executed instead. Mme d’Aulnoy herself evaded arrest by escaping from officers and hiding out in a church. It is unclear if she worked for a spy for France abroad, but eventually she returned to Paris in 1685. She went on to publish twelve books which included three pseudo-memoirs, two fairytale collections and three historical novels. She gained the reputation of historian and was known as Clio, named after the muse of history. Her work would be too fictionalised to be considered history today, but at the time there were looser definitions of what was considered a work of history.

Mme d’Aulnoy wrote her fairytales in the conversational style that one might hear in a salon. Her work used fantasy as a way to comment on the rigid structures of her time, often questioning power, marriage, and the role of women in society. Her fairytales were extravagant, filled with magical kingdoms, talking animals, enchanted disguises and intelligent heroines. Usually her stories centred on animal brides and grooms and featured love stories with great obstacles. Truly, her stories were written for the women of the salons, who could appreciate both the imaginative and playful grandeur of the tales and their sly critiques of societal norms. Her stories were artful reflections of the world her audience inhabited and offered salonnières a space to explore concepts of female agency, autonomy and desire.

⚜ Reflections: A Salon Discussion

Leisure, in its highest form, is not idleness but the cultivation of the mind in an environment of comfort. The salonnières had all the material comfort to afford this and, taking advantage of the privileges given to them in life, created spaces for the pursuit of knowledge and exploration of creativity that otherwise would have been inaccessible to them due to their gender or, at other times, their rank. To host or even attend a salon was to engage in a delicate art of conversation in which language is employed for both pleasure and critique. The salons were a testament to the power of thoughtful leisure and to the idea that time spent in reflection, debate, or artistic exploration is not time wasted.

Yet, the legacy of the salon raises a question most pertinent to our own time: who has the privilege of leisure? And at what cost does it exist?

I honestly do not think that it is natural to be free from the burdens of daily life. The effortless ease with which the salonnières and their guests indulged in thought and conversation, I believe, was an unnatural freedom, one made possible only through the suffering and exploitation of others.

Their ability to dedicate themselves wholly to art, philosophy, and (when we do put it into context, perhaps Molière was right, downright silly) wit came at the expense of those who laboured for them. Let’s not forget the peasants whose toil sustained their estates and yielded fat crops for them, their servants who managed their daily comforts and, more damningly, the enslaved people they literally owned, whose humanity was reduced to property.

The intellectual grandeur of the salons did not exist in isolation— it was built on a foundation of profound inequality and evil.

For all their brilliance, I wonder: could these same men and women have survived outside of the world that coddled them? Could they have endured the realities that most of humanity has always known? Could they survive and flourish under even our present fairly comfortable society where thought must coexist with labour and creativity must be carved from discomfort?

Their leisure was a gilded world that only existed because others were kept in chains. A most unnatural state made possible by the suffering of those who had no way of freeing themselves. For what is more unnatural: a life consumed by toil or a life insulated from it to the point where people forget work is part of the human condition? Maybe to be free of survival’s burdens entirely is not a mark of civilisation, but of imbalance. Many of those who gathered in rooms with decadent wallpapers and upholstered furniture spinning tales of enchantment could not have survived without the world that served them. And yet, they believed themselves to be the enlightened ones.

Their salons, for all their wit and brilliance, existed in a suspended reality. Their world was weightless because others carried the burden.

I am content with letting leisure be a dream (as I said in the beginning of this post) and to continue living my life, which is comfortable in so many ways, knowing that I am living through working.

Thank you for reading this far. I hope this was an entertaining read. Thank you to all the new subscribers since the last post.

If you enjoyed this post and are not subscribed, consider subscribing to get notifications of my upcoming posts:

This was a great read, oh how I should like to be a lady of leisure

Such a delightful read! Had to read it all in one sitting. It had me from the start 🩷