Yearning is the most exquisite kind of suffering. The feeling of being on the precipice of something great— on the edge of love, fulfilment, understanding— with no knowing if it may or may not happen. Yearning lingers between wanting and having, between dreaming and waking, between reaching and touching, and between life and death. Perhaps this is why yearning has been one of the most enduring themes in art.

To be human— to be living and conscious—is to want and yearning is one of the most profoundly alive expressions of emotion. To yearn is to reach beyond ourselves. We want something greater, something better than us, something gentler than us, something that is closer to the Ideal than us. We seek perfection in our Beloved. Yearning is the ache of desire for the Beloved, who is just out of reach for us. We want to obtain the object of our desires, to be near to it, to let it transform us. Sometimes we do get what we want and sometimes we do not. Knowing this is what makes the suffering bittersweet. Want itself is both pleasure and pain. Pleasure in the anticipation, in the hope, in the taking in of the sweetness of imagining what could be, but pain in the distance from our love, in the absence of it, in the knowledge that it might never be ours.

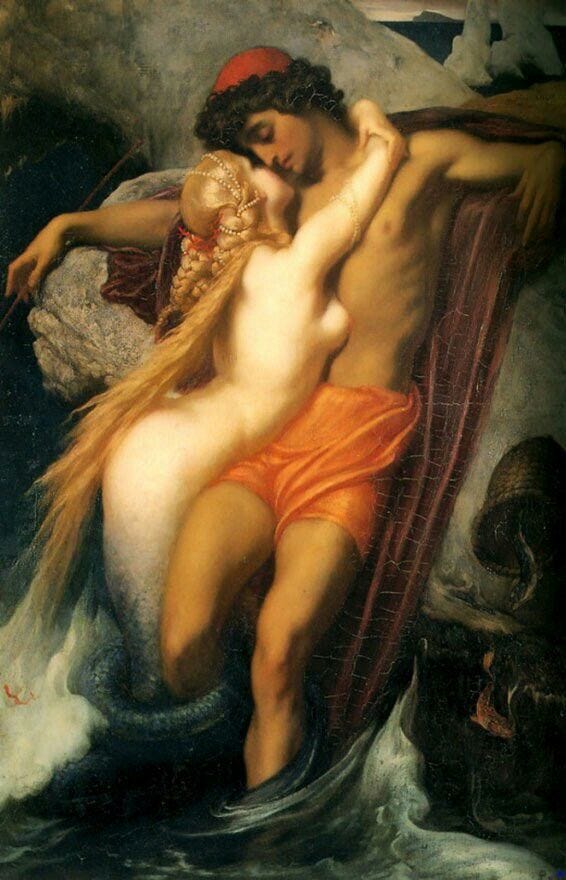

And when love is fulfilled, it does not lose its power— it transforms under the power of yearning, if it goes on. When the yearning of the wanters continues, the two can continue to long, and even in the closeness that has been attained, even in this union, the gap closes— souls are no entwined in a dance of perpetual longing. This too is yearning, but not in the absence— yearning in the presence. A sacredness of shared devotion.

Unfulfilled love, however, burns like a cruel, unquenchable blue flame. Never dying, never cooling. It rages unrelentingly, both harsh in its purity and constant in its hunger. It pulls at the spirit with no promise of relief, only endless aching want.

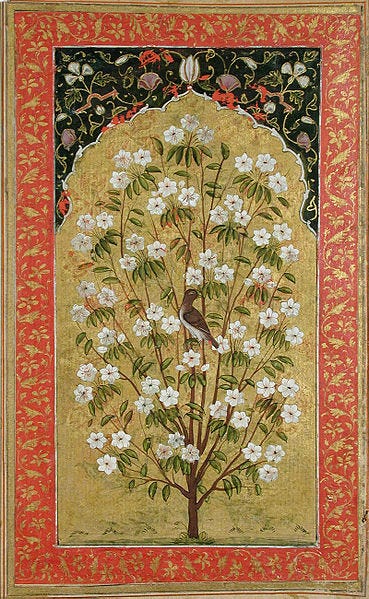

In Sufism, the mystical tradition of Islam, yearning for the Divine is referred to as talab (spiritual yearning) and ishq (divine love). For the Sufis yearning for unification with the Divine is a state of the most intense love— a yearning that pulls towards the ultimate truth. Talab is the want for something that can only be found externally, with an inner restless call that echoes within the soul. Ishq then is the manifestation of this yearning. It is said to be an overwhelming feeling of love that leaves nothing but pure devotion, unconfined by the boundaries of the physical world. This love extends into the infinite, with the lover continuing in their longing for that eternal union.

The journey of a Sufi is one of seeking and endless yearning, marked by both pleasure and suffering. Divine love, like all human feelings , is understood to have its mirror in the earthly realm. The depths of Divine longing reveal that true love is not only about fulfilment, but about the unending desire to be united with the Beloved. In Sufism, it is this love— this ceaseless yearning— that brings the soul closest to the Divine. The very act of yearning is what sustains the connection between the Lover and the Beloved.

Doves hold a deep significance in Sufism, often representing the soul’s yearning for union with the Divine in poetry. The dove, both gentle and pure, embodies the ideal of spiritual love in its most elevated form. Doves are monogamous and often pair for life. The dove, like the Lover, is constantly in search of the Beloved, flying through an endless expanse of yearning, only content when it is united with its Beloved.

Yearning and fulfilment

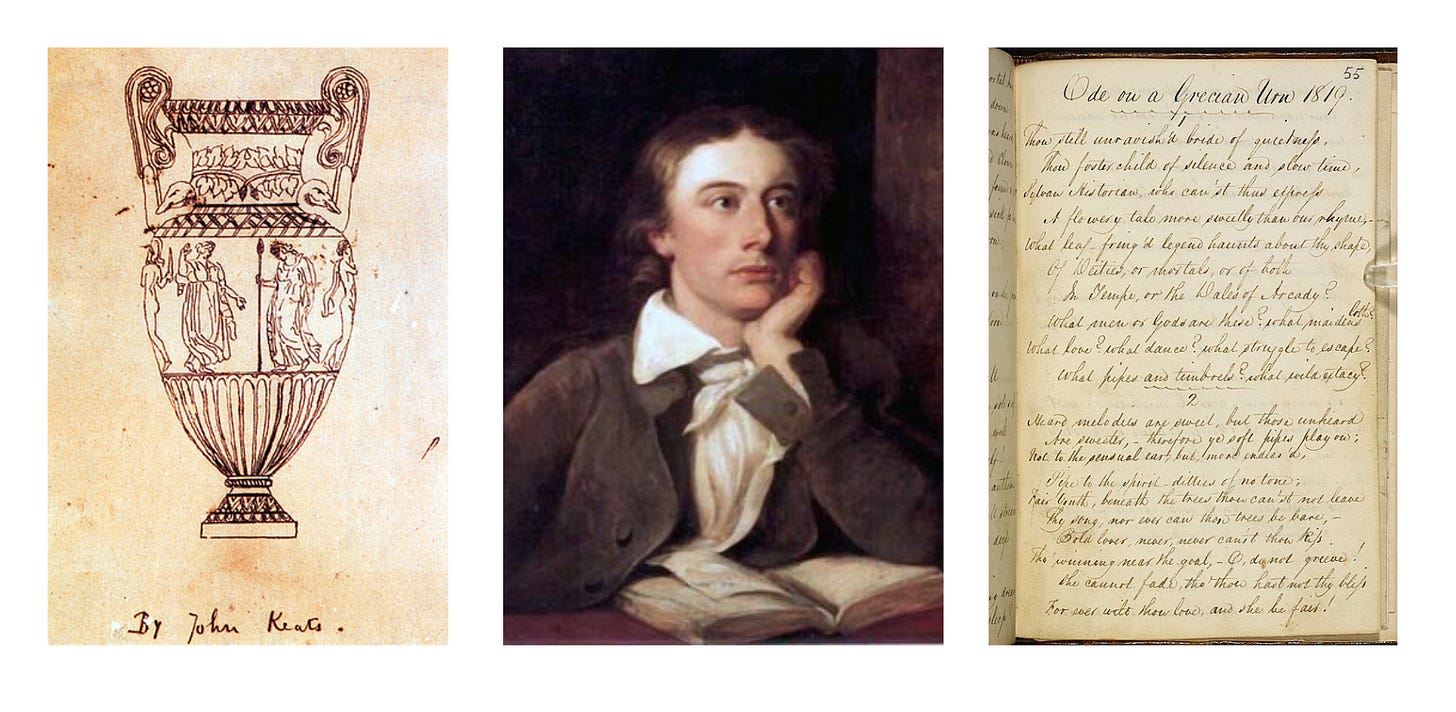

Bold Lover, never, never canst thou kiss,

Though winning near the goal—yet, do not grieve;

She cannot fade, though thou hast not thy bliss,

For ever wilt thou love, and she be fair!

Ode on a Grecian Urn (lines 17-20), John Keats, 1819

John Keats (1795-1821) in Ode on a Grecian Urn grapples with the warring natures of desire and fulfilment. The urn captures the eternal longing of the youth— he is destined to be forever trapped in the moment that comes before his pleasure— and the anticipation before his peak fulfilment. On the surface of the urn, the lovers are forever suspended in the intoxicating almost. There is beauty in this state, for the moment you have something, it begins to change. Attaining what you yearned for may bring disappointment, sadness because of its failure to stay constant, or it may simply fade away with time. But yearning? Yearning is forever.

Like Keats’ lovers on the urn, Tristan and Isolde are trapped in eternal yearning, barred from ever reaching fulfilment. Tristan and Isolde (or Iseult among other variants) are lovers from Arthurian legend, Tristan being a knight and Isolde a princess. The legend has had a lasting impact on European culture and many versions of the story exist. Very simply, the story goes:

Tristan was sent to bring Isolde to his uncle, King Mark, who planned to marry her. Tristan goes to Isolde and they start their journey to the King, however, on their way, they mistakenly drink a love potion, which makes them fall very deeply in love with each other. After Isolde’s marriage to King Mark, the two continue to see each other. King Mark eventually comes to know of their affair, so they escape into the forest. In a popular extended version of the story, Tristan is attacked by King Mark with a poisoned lance which wounds him mortally and Isolde dies of grief alongside him.

Their love was doomed from the beginning, hindered by honour, duty, and ultimately, death. But just like the figures on the urn, this is what makes their love so powerful. de Egusquiza in his 1910 painting captures the haunting endlessness of their yearning, Isolde has collapsed onto Tristan and their bodies are finally entwined. Not as they had longed for in life, as now they are united only by the stillness of death. Yearning is both fulfilled and left to unresolved— they have each other, but they are lost to the world. Their love, like the love of the figures on the urn, has escaped time and decay, but only because Tristan and Isolde themselves have perished. They exist forever in art, in the tragedy of what could never be fulfilment, but instead must perpetually be yearning.

I have been astonished that Men could die Martyrs for religion — I have shudder’d at it — I shudder no more. I could be martyr’d for my Religion — Love is my religion — I could die for that — I could die for you. My Creed is Love and you are its only tenet —

From: October 1819 letter from Keats to Fanny Brawn

In the end, yearning is the quiet flame that burns in our hearts, propelling us forward, always alive and never quite satisfied. For some, this feeling is a constant companion, a familiar ache that never fades. And for those of us who know it intimately, it becomes clear: to yearn, even if only a little, is to be human. We yearn for everything. To want something great and to want it desperately is part of who we are— who we are meant to be in the great cosmic order of things.

But perhaps the most important lesson is learning to come to terms with our perpetual hunger and the gnawing need for something greater, something more exalted. it is this longing that fuels our creativity (our life) here in this world.

Stillness is an enemy to be avoided. We must keep moving, ever in pursuit of what calls to us even if it remains forever out of reach. In the eternal rolling of yearning we find the truest expression of all we long for— forever just out of our grasp, yet always, always worth the chase.

Right now all posts on The Marchive are completely free. If you would like to show your support, consider contributing to my Coffee Fund over here.

(It’d be really appreciated and would fuel so much more writing!)

What a beautiful intellectual piece

yearning is the antithesis of the situationship and we all need more of it